I want to start by sharing a lovely compliment I received from a Facebook post by Joanne Elphinston.

I want to start by sharing a lovely compliment I received from a Facebook post by Joanne Elphinston.

“We are so pleased to meet Brett, an insightful Pilates teacher based in Stockholm. One of his aims for Pilates Intel is to question and challenge the teaching and practice of Pilates in order to encourage its development and evolution. We love that — Brett understands that for a profession to flourish, it must be confident enough to challenge itself, and dynamic enough to respond to the ongoing research in human movement.”

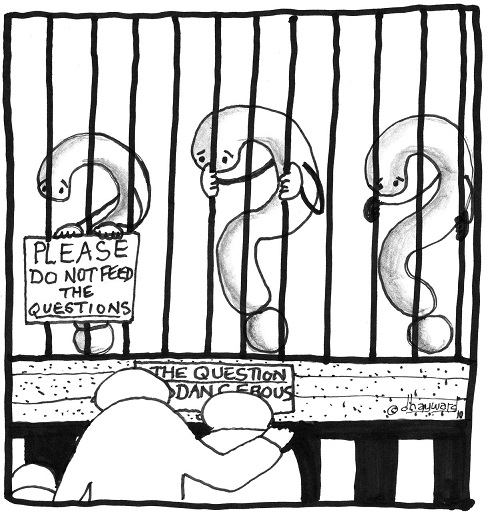

For a profession to have the confidence to challenge itself, it requires the members of that profession to have the capacity to respond openly and honestly when questioned. In two of my articles, Fatal Simplicity,and Is Position Enough,I questioned the assertions of two individuals. Prior to publication of each article, I always engaged the person whom I was questioning respectfully, and invited them to write a counter argument to my views for publication, the aim being that an open discussion would benefit all. In both cases, they were very kind and polite at first, but once they realized that I was serious in my pursuit, they abruptly dropped all contact. These cases are not exceptional; after a year of having a magazine, I have found this behavior to be prevalent in the Pilates field. Let me elucidate with another example.

Last summer I attended a workshop with a person that I will call Mr. Frenchtoast, and afterward I published a deservedly positive review. There was, however, a question and disagreement that I had with Mr. Frenchtoast in the workshop, specifically when it came to what he taught about preparing for the hundred.

In my training, we learned to prepare for the hundred by first bringing the legs into ‘tabletop’, and then taking the legs to the diagonal. Mr. Frenchtoast taught that in the original method, the hundred was approached by lifting the legs straight up off the floor. He then even added a good tip, which was to lengthen down and out from the legs prior to raising them into the diagonal position. He explained that by doing so the legs could be maintained in the diagonal position during the exercise with less exertion than if brought from above, as then the hip flexors would not be taken into use. All fine and good, right? He certainly gave a viable alternative, possibly superior to my own.

Nonetheless I had a question. I found that regardless of the method used to enter into the hundred, once there, the same amount of effort could be used to maintain the diagonal position. And so I brought it up in the workshop, expressing exactly that. As an answer I got “one movement is concentric while the other is eccentric”.

“Well yes”, I replied, “I can see that, but the question remains unanswered. How does your method actually lessen the amount of effort used in maintaining the legs in diagonal than the method that I know?” No answer came, and I understood that Mr Frenchtoast was not prepared to field the question, and did not have the presence to say so. Mr. Frenchtoast made it clear the subject was to be changed, and a quick turn of the back ensued. Not wanting to be a buzzkill, I dropped the subject as wished, and he went on to teach an otherwise fantastic workshop.

As mentioned, I penned a positive review, and it originally included our disagreement. I sent it to Mr. Frenchtoast for a first look, including in the letter my question in written form:

“Then I thought to ask you something else. Did you not say that when you bring your legs into the hundred directly up to the floor, by lengthening, then maintaining the legs in that position was possible without the use of the hip flexors? But that if you bring the legs from above, it was impossible to maintain that position without the use of the hip flexors. It was a point that I disagreed with you on, certainly bringing the legs to a position from different directions uses different muscles, but once there, I feel myself capable of maintaining them with the same muscular use and effort. I might be wrong, will look closely today in my workout.”

No answer was given in the reply. Mr. Frenchtoast requested in a friendly manner not to include our disagreement in my published article, as he was in an application process which might include Google searches, and the mentioning of it could jeopardize approval. As a token of good faith, the friendly Frenchtoast happily committed to take the matter openly some weeks in the future, in the form of a published friendly debate. The ebullient Mr. Frenchtoast even let me know that he would love to be a regular contributor to Pilates Intel, and to that end asked me to please write an invitation letter as evidence to the application authorities of him not being an overcooked piece of French toast.

Happy to help, and looking forward to a beneficial collaboration down the road, I agreed to do all that he asked. And the result? Mr. Frenchtoast had what he needed, and after a few letters informing me of delays, unceremoniously, and without a word – disappeared.

Because I had been impressed by Mr. Frenchtoast’s sincerity and enthusiasm, I initially suspected that only a catastrophe would prevent any non-performance in fulfilling the commitments he himself suggested, and so I feared that perhaps the poor fellow had drown in his syrup? But evidence of the good health of our hero was everywhere seen, and thus it was time for me to realize…… I had been dumped.

I was of course a bit sad, but there was no cause for deep worry for my stability. If I can persevere when Siri tells me she hates my Spine Twist, then even a spectacular display of zero-integrity by a Mr. Frenchtoast will not faze me. And so I soldier forward to complete my original line of questioning – alone.

And that is too bad, because one plus one has very well the potential to equal much more than two.

The problem I see with this Mr. Frenchtoast’s assertion is that it leaves out one very important attribute of our beings – the ability to adjust. Whether by raising the legs straight up off the floor (after lengthening the legs away as he instructed) or taking them down from ‘tabletop’, as we approach the end position, we are not stuck in using the muscles employed to make the trip there. And even if we use the same muscles in the maintenance of the position as those used in the transport to the position, we can use those muscles with a different quality. So I say, regardless the method used in the taking the legs to the diagonal, once there, the effort to maintain is, or at least can be, the same.

This is what I see in my own experience, and I am open to seeing things differently. That was the point of the question in the first place.

So let’s round back to the larger theme. It is often stated that the Pilates method increases the quality of life and robustness of the individual. And yet, the example in this article is one of many of a person with a clear ambition to be prominent in the Pilates community that lacks that very robustness to accept the challenge of honest, open questioning, for the sake of what is true and helpful. (Of course we are not talking about complete avoidance of being questioned; we are talking about situations where the person fears that he/she may be exposed as not being the expert he/she wishes to be seen as).

So let’s round back to the larger theme. It is often stated that the Pilates method increases the quality of life and robustness of the individual. And yet, the example in this article is one of many of a person with a clear ambition to be prominent in the Pilates community that lacks that very robustness to accept the challenge of honest, open questioning, for the sake of what is true and helpful. (Of course we are not talking about complete avoidance of being questioned; we are talking about situations where the person fears that he/she may be exposed as not being the expert he/she wishes to be seen as).

I in no way condemn ambition, nor the desire for prominence. I am not without them. However, to pursue success without fear and mediocrity, one must have the courage, and perhaps even the love, to say ‘I don’t know’ or even ‘Perhaps I was incorrect’ when the situation calls for it. This will also contribute to the health of the profession they say they love and are dedicated to. I leave it to a future article for a slightly philosophical and hopefully insightful discussion about why doing Pilates well will naturally result in the evolution of the individual so that they have the honesty, sensitivity and capacity to handle the challenges of being questioned.