Embodied Anatomy

Where do your limbs begin and end?

I invite you take a moment to consider this question before you read on – this could be very insightful and possibly tell you more than what follows here. There are many ways to answer this question. For example, if I would ask you to move someone’s arms in all possible ways, what would you do? You could consider what images come to mind or, when you use your limbs, what you actually feel.

Rather than talking about this, which is like trying to describe how a new fruit discovered on Venus tastes, I would much rather guide you through the experience. This will inform you in far clearer way, and impress upon you the profound nature and importance of the question. Check out my embodied anatomy album for explorations of a more “sense-full” approach to this kind of question.

The images you use as a reference for answering this question will certainly affect the way you use your limbs. Look at the stick drawings of many children, where there is a blob for the body and then stick arms and legs – many of us still move informed by this kind of body image.

In neuroscience, there is a defined difference between “body image” and “body schema.” I can ‘do’ a movement based on a description, an image, or by copying a teacher. Sometimes the movement ‘happens’ as a response to a question (“How do I most optimally meet the world in this moment?”). In that case, it’s not something I need to think about as my body is in a responsive state ready to answer the question. Before I ask this, my body schema is giving answers to far more important questions (like “Where am I?”) based on my impressions about my body and the world. What sense does it make to copy somebody else’s movement, even before I have asked this most basic of questions? To discover who I am, it’s helpful to have a reference about where I am, moment by moment – this is part of our basic reality-checking capacity.

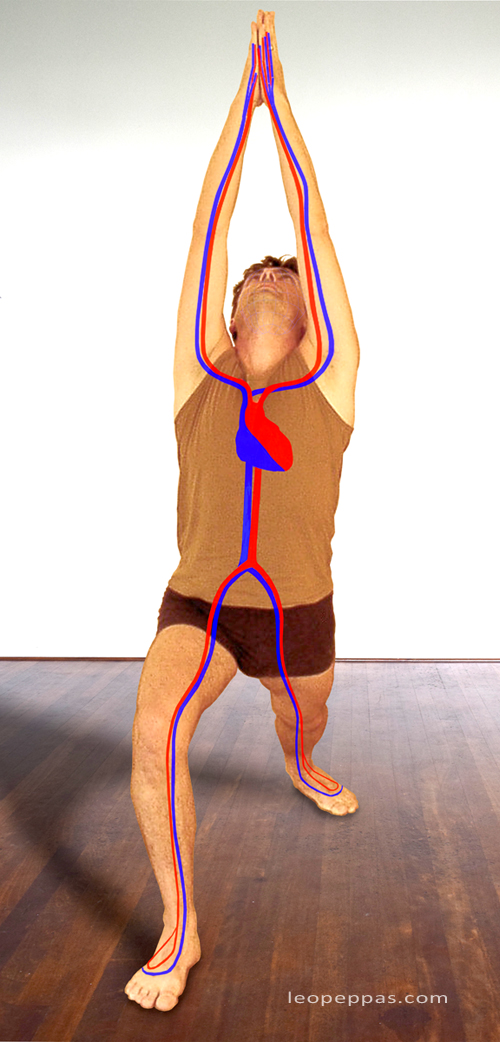

You will likely get a very different response if you answer the question by how you feel rather than an anatomical reference you may have learned. Anatomical references and images can both clarify and confuse our body’s natural intelligence. If we say the leg begins at the hip socket, or at the spine from the origin of the Psoas, or in the back muscles that connect to the connective tissue in the back of the leg and foot, or in a long pendulum that originates in the ascending and descending colon, we will get a very different experience from considering each perspective. What is actually useful in life may depend a lot more on more basic human experiencing, whether what touches our hands and feet is allowed to touch our core, whether our visceral sensations are allowed to be expressed through the structure of the container?

Learning to move through insufficient models, many of them having the human being completely removed, is not going to support a clear relationship with the world, confusing my experience of who I am and the nature of the world I am in relationship with.

When I reach, if my reach stops at the tips of my fingers, this will greatly impact the ease and quality of movement – compared to when the reach extends into the space around me. For most of us, our body image ends at our skin, but our body schema is not so fussy; it will even accept a tool, even an airplane, as being an extension of the body and it will include my kinesphere – the space in which I can move.

We are still constrained by an anatomical view that is 500 years out of date, the musculoskeletal images that we refer to for things like yoga/Pilates anatomy is a testament to this – it reflects our legacy of separating the mind and body, so that we can control and master it, more than it does the human being. When we separate the mind and body, it confuses us – if for more than a moment we forget that the most important element goes missing in this separation. Exclusion for the sake of ‘clarity’ is a risky business.

No amount of yoga or Pilates will touch us deeply enough if we don’t question the assumptions that have seeped into even this – the choices that were made many generations before any of us were even born. All tradition gathers dead wood, so it’s every new generation’s job to differentiate, to question, to strip back a practice to the basic essentials, to re-connect to a spirit of exploration and curiosity that allows continuing evolution. Basing our understanding purely on information, rather than being informed by access to processes that connect us to the basic nature of a human being, leads to an expression of the mind split from the body.

Maybe, we need a health warning on all anatomy atlases: “This is not the human body” – it is a figment of the anatomist’s fantasy, not the truth (at least the whole truth). As long as we remember this, it can be a useful reference, provided we truly understand what has been left out. This idea may seem radical, but what may be necessary in the face of an almost fundamentalist view of the world.

Our body is poetic in nature. When experienced only literally, we miss so much of the richness, we dullen our incredible capacity of experiencing, and we turn our backs on much of our intelligence. No wonder we seem to have lost some respect for what it means to be a human being and what the experience of an ecological body tells us about ourselves and our place in the world.

This is not a statement of the absolute truth, but a start of a creative process of questioning assumptions and seeing how this informs our relationship to the world and our body.

If you asked my advice, I would say to try vigorous African dancing. Play it loud and forget about the neighbors downstairs as you come into contact with the ground (you can blame me) and have plenty of space for your arms to move in the air. Then, when you are exhausted, pause to feel how your circulation connects your limbs to your heart, how the blood pumps to the periphery and how it swooshes back to the heart, what you put out and what you receive back in your relationship with the world – how you experience this dynamic relationship now in your body and in relationship.

Now tell me where your limbs begin and end.

Leo has been teaching yoga and movement for around 30 years. He is currently writing a series of yoga books, teaching workshops and mentoring teachers.

Leo has been teaching yoga and movement for around 30 years. He is currently writing a series of yoga books, teaching workshops and mentoring teachers.