Issue #437

Wednesday, August 28, 2024

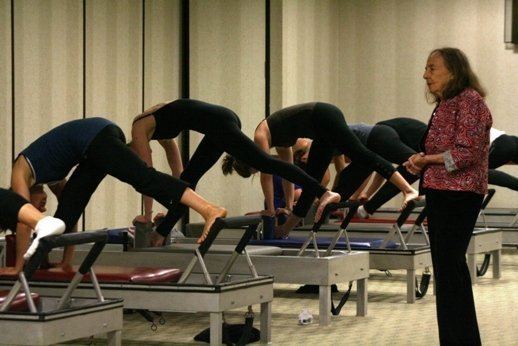

In Memory of Romana Kryzanowska

“You should be able to teach in an evening gown”

by Jennifer DeLuca

In a protective boot and crutches (not nearly as sexy as an evening gown and only slightly less efficient), I am in Vestby, Norway visiting a Pilates “sister.” I have not seen Hanne Koren Bignell since my days at Drago’s Gym 21 years ago. Hanne has invited me to teach a few of her students in her Summer Teacher Training Program. Three days before I left the states, I had an odd landing in a ballet class and fractured a bone in my right foot, leaving me unable to stand or walk without crutches.

Since I had to teach without my legs supporting me, I sat on the spine corrector in the center of Hanne’s lovely studio. This apparatus made it easy for me to swivel around to see everyone. Armed with experience and enthusiasm, I felt ready for anything. I began with everyone standing. Traditionally, we begin the Pilates Mat by lowering down to the floor without the use of our hands. As the students all crisscrossed their arms and legs in preparation, I said, “Wait. Stand parallel.”

Romana would frequently recommend that teachers-in-training sit in a cafe and “people watch.” As each person walked by, she would advise us to think of how we would apply the work to that person. If they had rounded shoulders, which apparatus would we include? Or if they are leaning to one side, how could we address that in their sessions?

In other words: See the body in front of you and decide how to apply the work.

I surveyed the room. These are people I have not met before. I was stuck sitting on the spine corrector with all of these new and different bodies around me, some on low mats, some on high mats. I was teaching them for the first time. I needed a moment to see the bodies in front of me. One person was leaning slightly forward. Another was looking down. Everyone was quietly waiting for my next word.

I made a simple request: “Shift your weight all the way forward toward your toes.”

Followed by a question, “Can you feel what changed in your body?”

“Shift your weight to your heels.”

“What changed now?”

“Keep shifting slowly. Shift less and less until you feel balanced.”

I am quiet. I observe.

“Reach your skull toward the ceiling. Reach your hips to your feet.”

“With that two way stretch, maybe you feel tone in your abdomen.”

Some students corrected a thing or two, some needed a bit more time.

Everyone had brought their mind to their body.

Someone was still looking down…

“Everyone look straight ahead. Make your sight line parallel to the floor.”

All skulls were then balanced on all spines.

“Widen your ribs, inhale. Narrow your waist, exhale.”

“Criss cross your legs and lower down to the mat with control.”

In that 1 minute intro, the foundation for a successful experience was established. I observed how each student took instruction. When I asked a question, it showed they needed to take ownership of the work and that I respect their own knowledge. A certain level of trust was built. They could believe that I was going to pay attention, give a clear instruction and move on.

Once The Hundred began, we were on a journey. Together.

Romana had a way of inviting people along with her when she taught. There was a spiritedness to her teaching. She taught from a place of joy. That joy flowed from her generosity. She gave her knowledge, humor and compassion without bounds. She taught from a completely authentic place that she intuitively understood was about a positive experience. She never seemed distracted, and the work was never about punishment, dominance or ego. She was having fun and you could feel it. There was something familial about it. Whether you were a ballerina, a 250lb film editor, or if you were bound to a wheelchair, you were always treated with the same care and attention. She was always registering your expression; looking for clues to assess where you were in your level of surrender and ambition. If she could feel you were holding back, she would find subtle ways to summon your commitment. Through her own excitement and words, she would buoy your confidence. Through simple things like, “Don’t say can’t!’ Say, ‘I’d like to someday do this!’” It was never about how much she knew and how little you knew, but instead it was about how much she could give and how much you could receive. Maybe it was the age she was at when I worked with her—in her 70’s— she could sense who her students were mentally, spiritually and physically, and seemingly by telepathy, but really from experience, she knew what to give them.

With all of that in mind, what I learned from Romana about cues is that they should be simple; if a person is stuck thinking about your words, they can’t move. And if they aren’t moving, they aren’t doing Pilates. I use the word “simple” to mean “clear and brief.” I remember the phrase “scoop et vous!” being in heavy rotation at Drago’s in the late nineties, which was a fun, spirited, French-ish way of saying “draw your abdomen in and up.” I’m sure that got replaced by something else in the following years. Romana would remind us that Joe used simple phrases too like, “In the air, out the air.” Or that your workouts should fit in everything you require in 45-55 minutes recalling his phrase, “An hour—in the shower.” When clients would ask Joe, “What is this good for?” He would quip, “It’s good for the body.” If an apprentice was teaching with too many words Romana would simply say to her mentee, “They don’t need to know all of that.”

As I taught my new Norwegian Pilates friends, I spotted that one of them could get caught up in her lordosis, and that another was not aware of her base leg in side kicks. Some things warranted singling out, “Anna in the blue, reach through your left leg a bit more.” Other cues applied to everyone, “lengthen your tail in the direction of your heels.” Sometimes multiple versions of exercises were tossed out—“First try with knees bent. To make it more challenging, try knees straight.” Simple cues allow me to do more individuating. My mind is at ease. I have mental space to observe. And I can spread myself across the whole class with enough energy to guide, encourage and enjoy it all.

Perhaps the biggest thing that Romana showed me , which I believe is the most important piece of how I mentor others, is that she taught like herself, not like carbon copy of Joe or Clara or anyone else. Through her example, I was liberated to teach like me. Not like her. She never said, “Say it like this…” You can channel certain people when you teach—like she often channeled Joe, and like I often channel Romana—but you have so much more to offer others when you teach like you.

A triathlete who competed at national and international levels, Catherine began her classical Pilates journey after a running accident resulted in a total hip replacement. During her rehabilitation, she discovered the power of Pilates in helping her get back on her feet. In fact, in many ways, she was stronger than she was before her injury. She realized, “I would have been a much better athlete had I known about Pilates 20 years ago!” It was then that she decided to pursue teacher training so that she could work with others to help them achieve optimum strength, awareness of movement, and flexibility. She is passionate about spreading the word on how developing a regular practice in classical Pilates is a life-changing and life-long pursuit — and it can be embraced by everyone.

Catherine recently retired as a professor of Asian art history and associate dean of the Graduate School at The University of Alabama and now teaches part-time for the university’s department of kinesiology, where she offers classes in indoor cycling and Pilates for university credit. She is a graduate of Streamline Pilates’ 450-hour intermediate-level teacher training program. She has been a certified Spinning® instructor for 24 years and a certified Personal Trainer for the past 20 years. In addition, she holds a Ph.D. in East Asian Studies from the University of Toronto.