Issue #442 – Wednesday, October 30, 2024

A Pilates History Lesson

Joseph Pilates’ Internment Years

by Jonathan Grubb

Most readers around the world will already be aware that Joseph Pilates was held in an internment camp during World War One (WWI). Joseph spoke about his internment; records confirming that he was interned at Knockaloe Camp in the Isle of Man are held at the Manx National Heritage (the Isle of Man’s main museum). 4½ years elapsed from Joseph’s initial arrest in the late Summer of 1914 until his eventual repatriation to Germany in March 1919. This four-part article will explore details of this time in Joseph’s life.

After the outbreak of WWI, a British Act of Parliament caused Joseph, along with other male German-born or Austro-Hungarian-born civilians who were residing in Britain, to be interned to prevent them from spying for the enemy.

To date, there has been no certainty as to the exact date of Joseph’s arrest, as the relevant Government records were destroyed sometime after the War. However, the following newspaper article could provide the exact date!

Prior to this newspaper article, any newspaper reference to the arrest of German civilians in Blackpool, where Joseph Pilates was arrested, related to named individuals. This article was the first to mention a large group of arrests in Blackpool and therefore does not include names, as there would have been too many to list. From the date of the newspaper, it is clear that these arrests took place on the 8th of September 1914. Following his arrest, Joseph Pilates was taken to Lancaster Internment Camp, a former wagon works (pictured below).

In an interview with Doris Hering in Dance Magazine in February 1956, Joseph stated that he spent about a year at Lancaster: the date of these arrests also fits in with his statement.

The following is an extract of a report on the Lancaster Camp which was made whilst Joseph Pilates would still have been there (the report was made by Mr. John B. Jackson of the United States Embassy in Berlin – his visit to England was made at the request of the German Government to inspect places where German prisoners were held). The report is held by the British National Archives.

Report on Lancaster Camp – February 1915

At Lancaster, which I visited on February 12, there were about 1800 men and 200 boys, many of whom had been taken from fishing boats at the beginning of the war, or who had belonged to bands of musicians. I understand that the boys under seventeen are to be concentrated at this camp, with a view to their repatriation. Here there were a considerable number of Poles and Hungarians — more than I had seen in any other camp, and there were also several men over 55.

The buildings used were an old wagon works which had been empty for about seven years. The floors are bad, but some of them are being made of concrete — as money becomes available.

The Commandant seemed energetic, interested in his work and anxious to improve conditions as much as possible. He has had a boxing ring arranged for the prisoners and has had gymnastic apparatus ordered. He has also arranged for school work for the boys and for other voluntary instruction — in electricity, the English language, and other branches.

The camp ‘major’ is a merchant captain who has the confidence of the Commandant and has been permitted to have a comfortable room by himself. (This captain spoke bitterly of the manner of his arrest and of the fact that he had been put in irons before being turned over to the military authorities.)

In the general part of the camp, the beds are raised and some of them are tented, as protection from the leaky roof. The better class prisoners occupy a separate building, where they have been able to arrange things with considerable comfort. The heating was satisfactory but the lighting was poor. The washing facilities were satisfactory, but there were only few baths. There were no water closets, the pail system being used, but here there were two sets of pails which were regularly disinfected — something of which I had seen no evidence in other camps. At night, however, the outdoor latrines are not accessible, and the pails are put in the sleeping quarters of the prisoners.

There were a number of small kitchens, one for each mess, which seemed to give general satisfaction as the men were able to have the food prepared in accordance with their individual tastes. Canteen facilities were adequate and there were few complaints made to me during my talk with the prisoners, except in regard to matters of historical interest having nothing to do with the actual conditions of their internment. The hospital was well arranged. It was quite full, there being a number of African patients (one case of “black water” fever and several of malaria). There had however, not been more than two deaths in the camp since it was opened. Men with venereal diseases or the itch were kept in a separate enclosure.

This is the second part of a four-part article on the 4½ years that Joseph Pilates was interned during the first World War. Part 1 covered the first portion of this period when he was at the Lancaster Internment Camp. Part 2 (below) and Part 3 (to follow in four weeks) paint a picture of his life at Knockaloe through diary entries, paintings, and photographs. Onward now with the story….

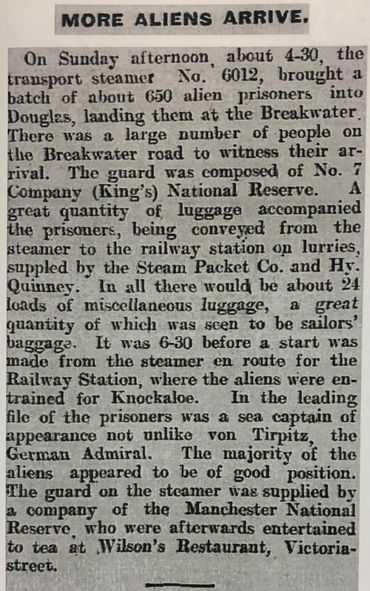

The International Committee of the Red Cross hold World War 1 internment records which include Joseph Pilates’ name, and evidence that in September 1915, Joseph, along with several hundred fellow internees, made the journey from England to Knockaloe Camp on the Isle of Man. An account of the internees’ arrival was given in a local Isle of Man newspaper:

One month later, another group of internees made the same journey, one of whom wrote about it in his diaries. It is a long read but gives great insight into how the internees felt and the resentment the British felt towards them. British resentment had grown drastically following the sinking of the Lusitania cruise liner in May 1915 (even though none of the internees were military personnel: only civilian men were interned at Knockaloe). Interestingly, the diary recorded that this group were interned in sub-Camp IV (the same sub-Camp as Joseph is documented to have resided; my own great-Grandfather was also interned in this sub-Camp).

Die Männerinsel “The Island of Men”,

by F.L. Dunbar-Kalckreuth

Finally, at about seven o’clock, the steep rocky coast of the ‘Man-Island’ arose from the waters, we saw the castle of the Dukes of Atholl, the former feudal kings. Giving no warning, the steamer’s horn suddenly began to blare out dreadfully; this was the last straw for others and myself, so that we simply flopped over the deck railing, and had to gasp in palpitation almost to the point of becoming unconscious.

Swarms of seagulls flew screeching past, very close to our heads. Finally, the ship was lying at the jetty. Volunteers were standing upfront, to bundle out the luggage. For two hours, we were not permitted to leave the ship. Checking and counting off in the pouring rain. Then soldiers as old as time took charge of us, surrounding us and leading us through Douglas (the capital town of the Isle of Man), up to the railway station. The Isle of Man had ceased to be a seaside resort, it had become an island of the imprisoned.

Then there was another railway journey. Once more, each compartment was allocated an armed soldier, then we travelled the full length of the island, out to the west. After an hour, the gigantic camp was already visible in the distance, the splendid goal of a splendid journey! In Peel, a small fishing port, it was a case of: “Out with you!’ And the well-known game of ‘counting-us-in’ turned up again. The heavens wept. Rain crashed down on us in a whistling, raging deluge. Grey, wet gloom was all around us.

Only Frida remained indomitable. Once again, he had the cloche hat on his head, and shouted out, “God, oh God, what are they getting me into?” But a Tommy knocked the hat off with his bayonet, and kicked it into the mud. “God, oh God,” Frida cried out in mock shock, “Oh no, it’s these ogres on this disgusting island-place.” Everybody laughed dolefully, but the farmer from Canada placed himself close to the Imitator in a shielding position, as the march now set off.

Every half-an-hour, the whistle blew for “Halt”, at which point between forty and seventy men flanked the roadside ditch and performed their impression of the water features at Villa d’Este. Frida always kept his eyes shut at times such as these. At last, we arrived and beheld endless rows of black-tarred wooden huts, which were inhabited by twenty-five thousand civilian internees. Nevertheless, everything looked abandoned.

The whole camp was split up into four lesser camps, each divided into seven compounds, and kept separate from the others by a triple layer of barbed wire, house-high and electrically charged. Everything here was on a purely military basis, just as in a prisoner-of-war camp. Each camp was governed by an English sub-commandant, each compound, of one thousand men, by a sergeant. The principle of ‘isolation’ had been applied here to its very greatest extent.

We new arrivals are put in Camp IV, Compound 1. Two of the huts here were already occupied, so we rushed across to the other eight, which were still under construction. A frantic struggle began for the corner seats. Bohltsmann with his Bavarian strength managed to grab one for himself and one for me, then the scuffle continued for palliasses (straw mattresses), which, however, smelt of damp seagrass; these were thrown down on the free spaces, and each man sat down as though on to well-earned laurel leaves.

But there was no time for resting. Trumpet calls rang out, and we had to report to Sergeant Blockhead in order to write — as one would in a fine hotel — one’s name into a list, for which one was given a number on tin plate. This number replaced one’s actual name. For the future I was: Two thousand, two hundred and forty-eight! If only this label had immediately erased my inner feelings as well and metamorphosed me!

This is the third part of a four-part article on the 4½ years that Joseph Pilates was interned during the first World War. Part 1 covered the first portion of this period when he was at the Lancaster Internment Camp. Part 2 (4 weeks ago) and Part 3 (below) paint a picture of his life at Knockaloe through diary entries, paintings, and photographs.

This is the second part of a long, detailed diary entry entitled Die Männerinsel “The Island of Men”, by F.L. Dunbar-Kalckreuth. We pick things up shortly after the new arrivals settled into their accommodations after their very long journey. Onward with the story ….

A huge, cruel-looking sailor, or whatever he is by profession, who had already been long interned in Knockaloe, now gave us the following encouraging words of welcome: “I welcome you to this beautiful place, fellow Fatherlanders, here you’re going to see for the first time what war means. And something else as well: We don’t have no ranks here. Money don’t mean nothing here. God don’t mean nothing. Them Englanders, they’ll soon show you what’s what here. Anybody making bother here, gets carted off to the stone quarry, not half! And there’s no treats for nobody. Stewed up bones every day. I’ll tell you this, though, if there’s any U-boats in that Irish Sea, you’ll get nothing to eat, and no post, neither. Do you know who lives in them tents over there? They are lepers, we buried one of them a couple of days ago. And if there’s any of you don’t like this-here paradise, and you clears off, there’ll be some merry shooting that day, not half! Look at this, my left hand’s bin shot off, too, that were when we’d set up an underground tunnel and were crawling through it one night, when somebody gave us away. Them Englanders sent that bloke off to a different camp. And now, if you choose me for Captain, we’ll see how things go, I’m on right good terms with old Blockhead, I just thought I’d tell you that.”

He watched us with a grin, to see what sort of impression his speech was making on us. In the meantime, it had turned black and foggy again. The lighting was still not working. One of two oil-lamps filled in as substitutes. In my hut there were a lot of Austrian Jews, speaking an awful double-Dutch. Their wet clothes put out a ghastly stink.

We had to have our big luggage poked through again, and I stored my diaries underneath my straw mattress. Finally, I had time to think about Rodenhaus once more; where were his quarters? Fortunately, I found out that he’d been put in the neighbouring compound. I hurried to the closed wooden gate, and true, he was standing on the other side of the barbed-wire entanglement, and waving. Shouting across is strictly forbidden. I gave the guard two shillings, and he gave us permission. Rodenhaus shouted across: “If we get shoved out on the meadow on Sunday, that’s when we can have our first talk.” I wrote something on a slip of paper, weighted it with a stone and threw it, but it didn’t reach its target. The stone and the paper fell into the dirt. The guard made threats, and after this sad reunion, we left each other.

How did things look now, in the new ‘holiday home’? Between the thirty straw-mattresses, there’s a table for the meals. Acrid clouds of smoke dim out the meagre lighting, but at least they block out the other horrible smells. Where can one get washed? Outside on the ploughed field, there’s a pump with three taps for a thousand men. To get to the toilet, which has no roof, you have to find your way across small duckboards, and when you’ve done that, you’ll find forty buckets next to each other with a sitting plank over them. Rain and cold air make sure that nobody stops in there for very long. Older ‘guests’ in this sanatorium resorted to little stilts to help them on their walk over the ploughed field, when they could no longer bear it in the huts.

Thus, everything had been catered for. Human civilised behaviour had triumphed, and once more we could see how marvellously far forward it had brought things in the twentieth century. For the evening meal, we had herrings. Then we played ‘My aunt, your aunt’, and you saw that money was the main business here; no nightclub would have been ashamed of the takings. All of a sudden, all playing cards had disappeared, banknotes had flown off into pockets; Sergeant Blockhead, armed with a baton, was out on his rounds; he thumped the tables and bellowed out: “Halloo, Halloo, Halloo, where are we? Lights out!” The gambling was over, and everyone crawled, most of them still in their day clothes, back into their straw beds.

How will things turn out, when the life of this place here really does get into your system? How dearly I should like to change souls with one of these more easily-pleased men. But all I can do is become a practical philosopher, go mad, or transform myself intellectually and physically into what people usually call perfection.

<<end of diary entry>>

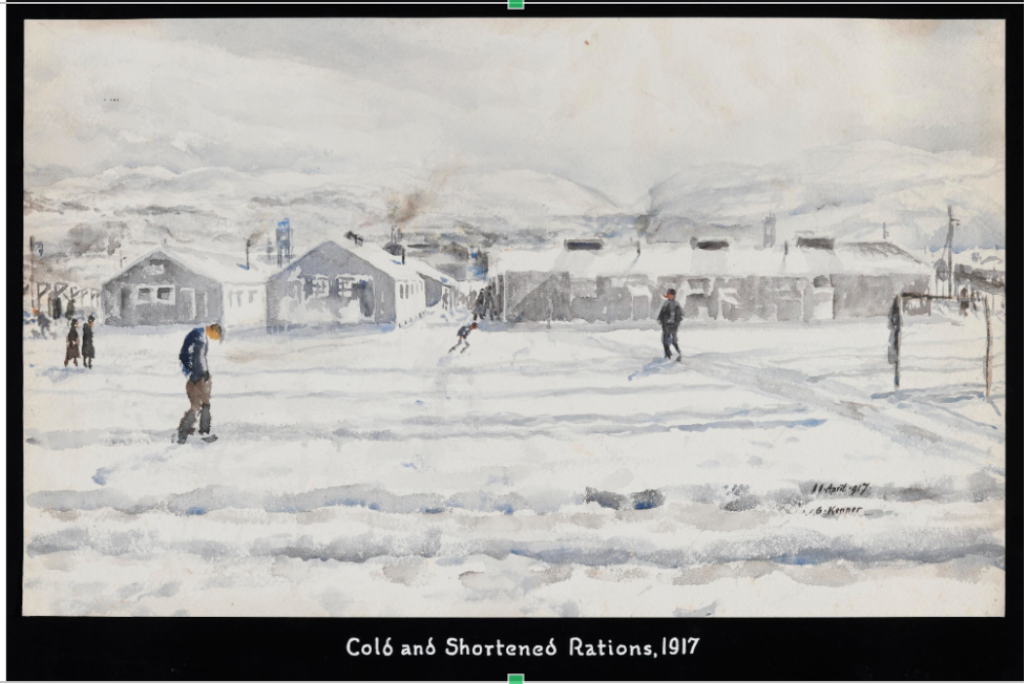

Conditions at the camp varied significantly. Internees could look forward to Spring and Summer when the rolling hills that surrounded the camp would be lush and green. However, Autumn and Winter were very different. The fields in which the living accommodation were situated could turn into a quagmire due to rain and the heavy football tromping daily through the sodden fields. The following watercolours painted by internees show what conditions could be like.

Image courtesy of Manx National Heritage

Image courtesy of Manx National Heritage

Knockaloe Internment Camp was “well described by a visitor as being like a glorified chicken run. Not only were the huts suggestive of enlarged hen-houses, but the aimless wandering of the men round and round the compounds, in dust or in mud, according to the weather, brought to mind the scratchings of cooped chickens in their already well-scratched-over soil.” (“St Stephen’s House, Friends’ Emergency Work in England 1914 to 1920” by Anna Braithwaite Thomas and others).

Photograph of Knockaloe Internment Camp – courtesy of Manx National Heritage

This is the fourth and final part of an article on the 4½ years that Joseph Pilates was interned during the first World War. Part 1 covered the first portion of this period when he was at the Lancaster Internment Camp. Parts 2 and 3 painted a picture of his life at Knockaloe through diary entries, paintings, and photographs. Now in part 4, we look at how Knockaloe shaped and changed him – leading to the origins of the Pilates method we know today. Onward with our story ….

Approximately 23,000 men were held at the Camp within an area covering only 22 acres (this is less than 17 British football/soccer fields). At the outbreak of the War, Britain was a very different place than it is today and attitudes to German, Austrian, Hungarian, Italian and Turkish (described at that time as “enemy aliens”) were very strong. Joseph arrived by boat on the island in the dark of night when locals were less likely to see the new internees. He was then transported by steam train to the Camp, to awake the next morning enclosed within his new barbed wire-surrounded home.

How did Joseph deal with the challenges he faced during that time? Lolita San Miguel (first generation Pilates teacher certified by Joseph Pilates) recounted to me that Joseph did not speak much of his time on the island. However, she remembered that when she did ask him about it, he always said that he was actually very glad for the time he spent on the Isle of Man as it gave him the time and opportunity to work on his method, which he may not have otherwise had.

Joseph displayed an admirably positive attitude in the midst of a very tough situation. Several others fared less favourably with “barbed wire disease” (now known as “depression”) which was a serious issue, with a number of internees ultimately taking their own lives.

Dr A.L. Vischer, who was an independent visiting inspector of internment camps and visited the Isle of Man during WWI, had a special interest in mental health. In respect to his visit to Knockaloe Internment Camp, he stated:

“The long duration of internment produces in many of the inmates a certain psychosis which the mental specialists term as “barbed wire psychosis”. This is characterised by a gradual loss of memory, irritability and a continuous concentration of the mind upon certain aspects of camp conditions, and it is very probable that this barbed wire psychosis will leave its traces on the men for the rest of their lives. It is the same in Prisoner of War Camps all over Europe, and our mental specialists have ample opportunity to study it amongst the prisoners interned in Switzerland. I would suggest an expert investigation to be held by mental specialists, say by a neutral medical commission, who could possibly give some advice in this rather serious matter.”

Camp authorities tried to help alleviate boredom by creating tennis courts, a football pitch, gardening areas and agricultural areas (which also helped supply food), outdoor recreational space, manufacturing space to produce tables and chairs etc., educational libraries in each sub-Camp and activities such as gymnastics, gardening and boxing competitions.

Confinement was overshadowed with no knowledge of the future outcome or duration of the War, coupled with severely restricted food and resources (albeit, during the War, food and resources were also restricted for those who were not interned). The living conditions were not pleasant and men were dying around Joseph, not only from illness, but as he observed, from lack of hope and stimulation in life. However, Joseph used the time as an opportunity to develop his method towards radically improving the lives of the sick, injured and increasingly hopeless men around him.

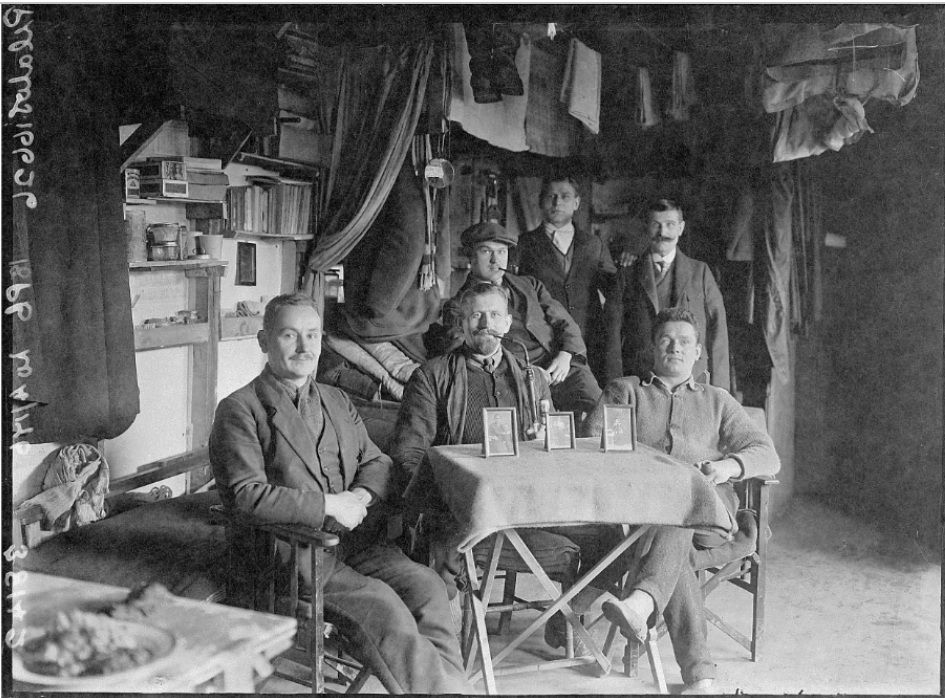

Joseph Pilates seated right, photographed at Knockaloe Internment Camp around 1917 Image courtesy of Manx National Heritage

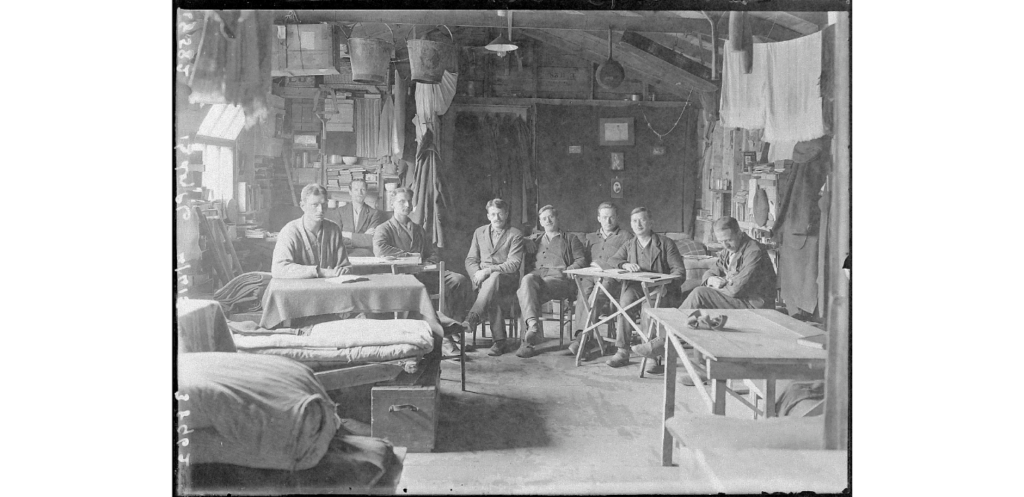

In Joseph’s interview with Robert Wernick for Sports Illustrated in 1963, he is reported as having said that he was inspired by the cats at Knockaloe. As a cat lover myself, I am sure that not only were these cats a source of inspiration but that they would have brought comfort and companionship to many internees who were missing families and friends. The following image shows the inside of one of the accommodation huts, giving an insight into how cramped they were and how every available piece of space was utilised. Seated right is an internee holding one of the cats of Knockaloe.

Image courtesy of Manx National Heritage

Joseph was finally released from Knockaloe Camp on 16 March 1919 when he was transferred to Alexandra Palace, London, UK, which was used as a holding camp prior to internees being repatriated to Germany. Many internees were never given permission to remain in England, despite having wives and children there: only a small percentage were given permission to remain. Those who made an application to stay in Britain waited months to receive a decision as to whether they were given permission to stay.

Little remains of the no-longer-required Knockaloe Camp today. The fields were returned to agricultural use immediately after the Camp was dismantled. The photograph below was taken last year overlooking the fields that contained Camp 4, where Joseph was housed, the barbed wire a poignant reminder of what happened here over 100 years ago.

The fields of Knockaloe, 2023 – copyright Jonathan Grubb

Due to the tireless efforts of a group of local individuals, the history of Knockaloe Camp is being preserved in a visitors’ centre and museum close to where the Camp was situated. They have also published a very informative website which covers all aspects of the Camp: knockaloe.im

As well as displaying many artifacts and photos from Knockaloe Camp, the Centre also displays an incredible scale model of the Camp, constructed to give visitors a clear impression of the layout and size of this once small town that has now vanished.

Image copyright Knockaloe Visitors’ Centre

Jonathan Grubb was born in England in 1962 and has lived on the Isle of Man since he was two years old. His great grandfather Jakob Grub was interned on the Isle of Man until 28 August 1919 in the same camp as Joseph Pilates.

In his younger days Jonathan was a keen amateur sportsman and particularly excelled at football (soccer), representing the Isle of Man in international games on numerous occasions. An anterior cruciate ligament injury sustained towards the end of his playing days led him to discover Pilates and he has been a passionate practitioner ever since. He has traveled to various countries to attend conferences and courses and been fortunate to be mentored by very experienced local teachers.

Having previously been an advanced instructor for several years in the Wu family style of tai chi chuan, Jonathan is currently studying to become a Pilates teacher with MKPilates and his teaching has been enthusiastically welcomed in classes throughout the island already. More on the story of Knockaloe Internment Camp can be found at knockaloe.imCheckout Jonathon’s Facebook page Joseph’s Legacy – Pilates 100 +!